Documenting our Humanity

Well, dear Canan, it started.

Please pray for all of us.

These are the words my colleague, fellow literary translator Hanna sent me on Thursday morning 24 February 2022 from Lviv, where she lives with her daughter, her son and her husband. Her e-mail followed an exchange we had the day before. Since October 2021, Hanna and I have been working on a literary translation project, with me guiding her in her journey as a translator working from Ukrainian to English. She has a lot of experience the other way round but needed further support and encouragement to work as a translator from her mother tongue into English, a language she is totally equipped to write in and translate into. As a translator and a writer who has forever been expressing myself outside of my so-called mother tongue, it has been a natural continuation of my own practice to encourage Hanna to break all the boundaries of definitions such as “mother tongue” or “native language” that many times are used to put us in boxes and stop us from expressing ourselves freely. As Hanna and I were working on her translation sample, I reminded her that she was allowed to be creative in English, something she was afraid to do at first, especially under the pressure that English wasn’t her “mother tongue”. The more I recognised her fears, the more I championed her to break free. Hanna doesn’t need my permission to be creative, and if she was waiting for it, I told her that if we do literary translation, we have permission. Literary translation is a creative act. Language needs our creativity.

Throughout our exchanges we looked at the opportunities and challenges around literary translation. We focused on the questions the novel she is working on posed. It is the story of a young man with Tourette’s Syndrome, so we dived into the vocabulary of disability in English, looked at what is written and published, what stories and which writers in English come from these communities and how they can support us finding the language to use in this particular translation. To become part of the English-speaking literary landscape with a story of disability from Ukraine.

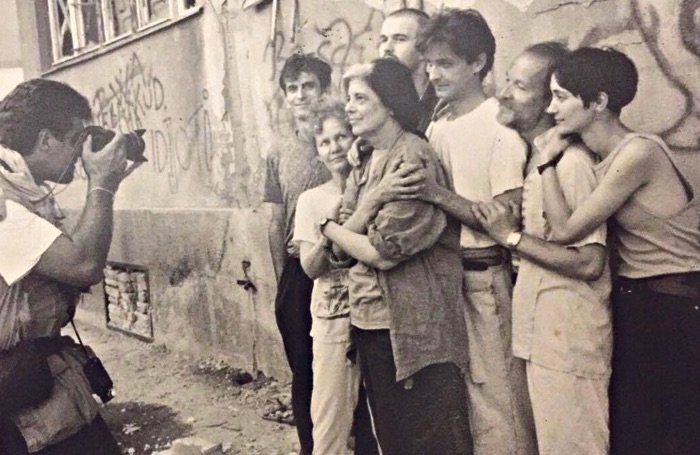

Odessa, September 2017. Photo by Canan Marasligil

A week before Russia attacked Ukraine, Hanna and I were still talking about all this, about why it is important that she presents this book to publishers at the upcoming London Book Fair, to offer a lesser-known narrative of Ukraine and hold a space where not all stories are about conflict and Chornobyl. That this particular story focusing on disabled people made invisible by society is worth translating and publishing. We were making a plan, thinking of a strategy, looking at all the opportunities outside of the book for the book to exist in her translation, so it could find its readers in English.

Since Thursday 24 February 2022, our exchanges switched to sharing links and resources on how to support the Ukrainian people, fund charities, sign petitions, donate money, share contacts… Hanna told me she was lucky, that they managed to leave the city to take shelter in their relatives’ home in the countryside. We are safe. She wrote me, and that whenever she can, she is translating for various media as a volunteer. I dare anyone to ever question her urge and capacity to translate into English.

Hanna and I don’t talk about translation right now, yet, what we do, in its essence, is translation: our exchange is essential as we share knowledge, emotions, data. My role as a receiver is to make sure her words, her story, her knowledge and experience, get to the people who can in turn respond with support and solidarity. I am also here to show her that I care. Hanna and I are both translating; we are using our most important skills as translators to try to make a difference; to influence a narrative, and to create spaces for solidarity and empathy.

In between my conversations with Hanna, I dived into my personal photo archives from Odessa, where I was in September 2017 as part of a cultural exchange programme. I took many beautiful pictures and videos, Odessa’s light is absolutely magnificent, and the people I encountered, the kindest. I really felt home in Odessa.

Among these pictures, a series caught my attention: I took several photo and video shots of a signpost showing distance to different cities. Usually these are more entertaining than informative. The light made it difficult to read the name of the cities and the distances. Like any other place on earth, Odessa is close and far to many other places. Why did I insist on capturing this signpost? Materialising distance to remind myself how close I was to geographies I know and don’t know? To feel a connection to those places through the distance that separates us? Does it really matter, where we are geographically based or where we were born? Does it determine our value as a human being, and the level of empathy we deserve to receive, especially in times of war, when violence is inflicted on us?

In her poetry collection LANDIA, Celina Su writes the following verses:

To stand on the right side of the border, to hurry east. Still, fingers

as if

One possessed fading papers. Folded like a road map—

Pressed in plastic bags lined like onion skin. What documents

me human.

Celina Su’s poetry collection is about movement, migration, national borders, written in a context of America’s rising xenophobia. These verses stayed with me since the first time I encountered them.

I keep refreshing my Twitter feed with #IstandWithUkraine #WarinUkraine

Then I find more feeds, this time with #AfricansinUkraine

I think of Su’s verses:

What documents

me human.

Next to the disturbing accounts of racism against black people and other people of colour at the Ukrainian borders, we have also seen how Western media has reported about Ukrainian refugees, documenting them more human than those fleeing all the other places of war on the planet where according to their deep-rooted racism and white supremacy, they are used to violence and oppression. Using descriptions such as “blue eyes and blond hair” and creating a language of proximity based on binaries such as “them” and “us”, they erase any possibility for empathy beyond nationalism.

What documents

me human.

I turn to Susan Sontag and her essays about Sarajevo from 1993 and 1995. Sontag went to Sarajevo as the city was under siege to direct Samuel Becket’s Waiting for Godot with local actors. Her thoughts on how Western countries chose to ignore Bosnia at the time because the populations that were being murdered were Muslim, still scratches deep and unhealed wounds.

Drawing parallels between wars falls beyond my area of expertise and knowledge. I do trust Aleksandar Hemon, Bosnian writer who has lived in the US since 1992, when he tweets:

“Make no mistake: the Russian strategy relies on civilian atrocities. The more desperate they are to complete this stage of war, the more brutal the attacks will be. The trajectory is toward genocide. The Ukrainians are fighting for survival. There are no two sides here. Putin has learned a lot from Milošević and the Serb Army’s operations in Bosnia. No wonder Serbia today is enamored with Putin–he is Milošević + Mladić square.” (@SashaHemon, 27/02/2022)

It is no wonder I instinctively turned to Sontag’s days in Sarajevo to find either understanding or solace, or both.

In her essay on translation from that same period, published in Where the Stress Falls, Sontag writes that “Translation is about differentness. A way of coping with, and ameliorating, and yes, denying difference —even if […] it is also a way of asserting differentness.”

She writes this in the context of the play, Waiting for Godot being translated again in Sarajevo. Not because the actors couldn’t understand the existing translation, but because they needed a new version, a local, Bosnian one, in this specific context: to assert their differentness from their oppressor.

“If someone did a new translation in Belgrade, would that be different too?”

“Maybe,” he said.

“And that new translation would be different in a different way from this new translation?”

“Maybe not.”

“Then what’s going to be specifically Bosnian about this translation?”

“Because it’s done here in Sarajevo, while the city is under siege.”

“But will some of the words be different?”

“That depends on the translator.”

Susan Sontag with the cast of Waiting for Godot, during the siege of Sarajevo in 1993. Photo by Annie Leibovitz

It always depends on the translator, and the context in which we translate. “Every work of translation carries a text into the literature of another language,” writer and photographer Teju Cole writes in his beautiful essay “On Carrying and Being Carried” published in his latest collection Black Paper. Writing in a Dark Time. I love how he uses the verb “to carry”, which holds so much care, tenderness and effort in its definition and existence. While celebrating translation and applauding the work of literary translators, Cole avoids falling into the trap that literature and art make us more empathetic by definition. He brings a much-needed nuance into the idea of empathy, through this act of carrying, illustrating how translation is a way to carry from one shore to another, just like a boat carries refugees, or busses – right now, carrying Ukrainians to its neighbours’ borders. Yet, these same boats get drowned as we ignore them and erased bodies get washed away on European beaches, bodies later replaced by breathing, visible ones soaking in the Vitamin D they’ve been lacking throughout the year. As a society, we have decided which bodies are more humane than others. As I write these words, black refugees from Ukraine are being refused crossing the borders that may be their only chance to remain alive.

What documents

me human.

Cole writes: “We all live and die under essentially similar sovereign arrangements, are all subject to the same international banking system, the same alliances among rich nations. We are all citizens under these inescapable powers, but not all of us have our rights of citizenship recognized.”

As translators, we will not change the world and we cannot ignore that the powers at play are too immense for us to influence. What we know, what we do is: language. We do have influence over language, at least in the translations we work on, such as Teju Cole’s Italian translator did, enriching the Italian language because of her knowledge, experience, understanding of Cole’s text and the context in which he writes:

“Gioia Guerzoni, who has translated four of my books into Italian so far, has worked hard to bring my prose into a polished but idiomatic Italian. In 2018, she translated “The Blackness of the Panther.” It wasn’t an easy text to translate. In particular, the word “Blackness” in the title was a challenge. To translate that word, Gioia considered nerezza or negritudine, both of which suggest “negritude.” But neither quite evoked the layered effect that “Blackness” had in my original title. She needed a word that was about race but also about the color black. The word she was looking for couldn’t be oscurità (“darkness”), which went too far in the optical direction, omitting racial connotations. So she invented a word: nerità. Thus, the title became: “La nerità della pantera.” It worked. The word was taken up in reviews, and even adopted by a dictionary. It was a word Italian needed, and it was a word the Italian language – the Italian of Dante and Morante and Ferrante- received through my translator.”

Language creates, imagines, documents.

The current discourses being constructed and shared across Western media, using racist and white supremacist language to create a hierarchisation of our humanity make our work more urgent than ever. Next to these problematic and highly dangerous narratives, we also, with all our best intentions, tend to turn to nationalism and waving flags in solidarity. Writer and Human Rights professor Ayça Çubukçu rightly shared on Twitter that:

“We need an internationalism that does not reflexively resort to waving the flag of a nation-state—even under attack— as the primary form of expressing solidarity. We need to think beyond the nation-state form in situating “our” side in war and peace alike.”

A tweet to which historian Edin Hajdarpašić replied with a video of James Baldwin in conversation with Paul Weiss in 1969, discussing socially constructed but systemically real categories.

As translators, our task is to create language beyond definitions of identities, beyond distances. While acknowledging the contexts we live in, which are spewed with discourses of division and hatred, it is in our power to make choices that don’t replicate binary understandings of the world into “here” and “there”. We must refuse to participate in the hierarchization of our humanity. Such hierarchization starts with language. Could it end with language, I am unsure, but I believe that we must try to influence language, because right this moment, there are people standing in borders wondering: what documents me human? and as we turn our back on them, they will die.

I dedicate this talk to literary translator Hanna,

to the people of Ukraine,

to all the people across the world who are living under war and persecution,

to everyone who has become a refugee.

Amsterdam, 01 March 2022

This essay (first published by Read My World) is adapted from a talk Canan Marasligil gave on 28 February 2022 to the participants of a translation project organised by Expertisecentrum Literair Vertalen (ELV) and the Vertalershuis Amsterdam. From February until June 2022, a group of emerging translators working from English to Dutch receive mentorship to translate the short story collection Lot by Bryan Washington. The project is organised by ELV and the Vertalershuis, in partnership with publisher Uitgeverij Nijgh & Van Ditmar.

Writer, Literary Translator, Artist based in Amsterdam.

Canan (she/they) publishes The Attention Span Newsletter, taking the time to reflect, to analyse and to imagine our societies through writing, art and culture; and City in Translation, fostering discourse and conversations around the art of translation.