Steve McQueen, The Translator

In March 2012, I walked through Blues Before Sunrise, an installation by artist and filmmaker Steve McQueen in Amsterdam’s Vondelpark, together with someone whom I hadn’t seen in a long time and who used to just be a colleague from Brussels. The 275 streetlamps in the park, emitting blue light instead of white, didn’t only transform the night, it turned acquaintance into friendship. McQueen had extended an invitation to us, to engage with one another in more depth, in a place where we may normally just have walked through.

I have always admired Steve McQueen’s work. He is well-known for receiving an Oscar in 2014 for Twelve Years a Slave, and the Turner Prize in 1999. To me, he has always been the artist who shook me to the core with Shame, a film he co-wrote with Abi Morgan, starring a poignant Michael Fassbender.

Most recently, I watched McQueen’s first feature documentary, titled Occupied City/De Bezette Stad, inspired by the book Atlas of an Occupied City – Amsterdam 1940-1945 (2019) by Bianca Stigter, who also wrote the screenplay. The film lasts 262 minutes, so it does ask some organisation if you wish to see it in a cinema (Oppenheimer and Killers of the Flower Moon have trained me well, even if Occupied Citywas an hour longer than these films). I watched the Dutch version, narrated by Carice van Houten (better known by non-Dutch speakers for playing Melisandre in Game of Thrones). I needed to engage with this film in the Dutch language, which I believe is also the original language the filmmaker chose to make his film in, and I wanted to honour that (a version with English narration also exists).

In four and a half hours, the film takes us through contemporary Amsterdam, more specifically the city in its Covid era, with its empty streets, its masked protagonists, and those who refused to mask and went out protesting the government restrictions. We go inside people’s houses, on squares that have changed names, we stand on monuments: Holocaust and slavery memorials, we attend climate and anti-racism protests. All this happens while stories from the Second World War are being narrated in a voice over. On each one of these specific places: each address, each square, every street we are shown, people from the past blend into our present. At no point does McQueen use archival footage, not even a photograph on screen. We are never dealing with the past, but always with the present. As William Faulkner once wrote: “The past is never dead. It's not even past.”

When I first moved to Amsterdam fifteen years ago, I had written an essay for a French publication about how I had started to call not Amsterdam, but Mokum, home. This essay has evolved into a recent one I have penned in English for online magazine SKUT:

Today I call Mokum home, a place I knew no one when I arrived.

For someone who finds themselves in movement (between languages, places, imaginations), it might be strange that I choose to call Mokum home today. And maybe it is because I am not really home anywhere but in writing and translation, in that constant movement, that it feels right to call Mokum home. Mokum in Yiddish means ‘place’ or ‘safe haven’, derived from the Hebrew makom. The names of certain towns in the Netherlands had been abbreviated in Yiddish; Mokum Alef for Amsterdam (‘city A’), Mokum Dollet for Delft (’city D‘), or Mokum Resh for Rotterdam (‘city R’). Today, the word Mokumis used without the Aleph to refer to Amsterdam. For fifteen years I have lived in this city and I have found a home in the former Jewish quarter of Amsterdam, which had been partly destroyed and was rebuilt following the Second World War, when many Jewish families did not return.

I have linked this exploration of identity and belonging to my vision of translation (which is what the essay is SKUT is all about). Having found myself in the former Jewish neighbourhood of Amsterdam had transported me into a history that was not mine and yet, I felt deeply connected to. Every single street I was walking in, every monument I encountered, it all carried the heavy stories of the past, including the flat where I have been living for fifteen years.

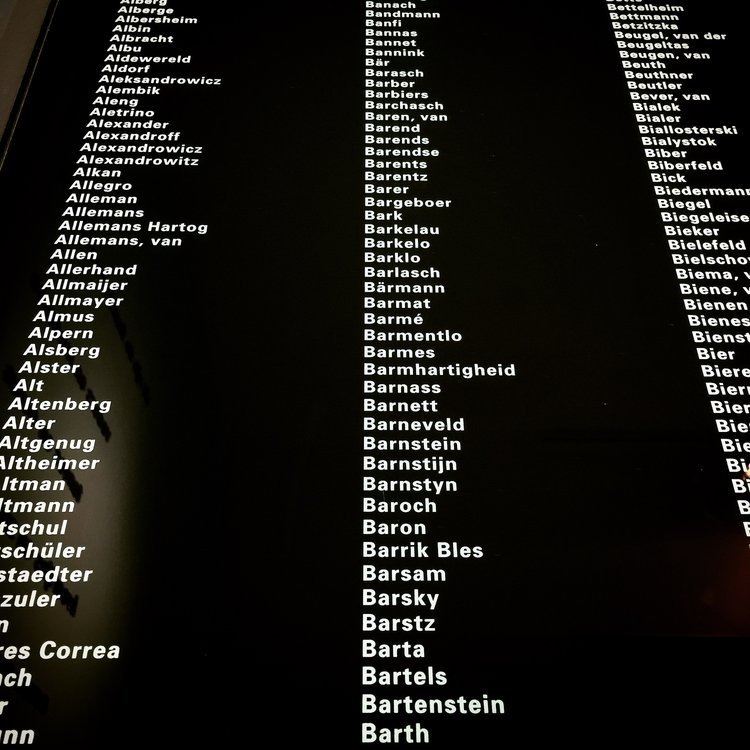

Every morning I get up, every evening I go to bed in an apartment where a Jewish family lived. All were deported. Father, mother and six children. Barmhartigheid was this family’s name. Barmhartigheid means ‘mercy’ in Dutch. All the members of the Barmhartigheid family were deported and executed in Auschwitz in 1942 and 1943. The ‘mercy’ family, the ‘charitable’ family. In memory of the role played by the citizens of Amsterdam during the Second World War, in particular with the strike launched by the dockers, Queen Wilhelmina presented on 29 March 1947 the motto which has since become part of the city’s coat of arms (and can be translated as Valiant, Determined, Charitable/Merciful): Heldhaftig, Vastberaden, Barmhartig.

I used to go pay homage to the family when the names of all the Jewish people from the Netherlands who were killed in Nazi camps were still listed inside the Hollandse Schouwburg, where deportations were organised from. Since 2021, the 102,000 names have moved to the National Holocaust Names Memorial, the opening ceremony of which Steve McQueen features in his film. My family’s name is also there, I showed my friend who is also a literary translator and a poet, as we walked by the monument the other day. “Rahman” she said, I looked at her, “oh! Rahman! et rahmetli, aussi”, “Mais oui” she exclaimed. We stood silent for a split second before we parted ways in a warm embrace.

I had never made that connection between the Dutch word Barmhartig and the Arabic word for merciful, King and gracious, which in turn had given birth to the Turkish word for the departed. I needed my multilingual friend to open and hold that space for me. My connection to this place had gained another layer of depth. Just like McQueen does in his film, showing us Arabic-speaking residents of an Amsterdam neighbourhood playing pétanque while Carice Van Houten narrates another story about a building that used to stand there, or people whose souls caressed this particular soil.

In La Mémoire, l'histoire, l'oubli (Paris: Le Seuil, 2000), Paul Ricoeur wrote: “il est des témoins qui ne rencontrent jamais l'audience capable de les écouter et de les entendre.” (There are witnesses who will never encounter the audience that would be able to hear and listen to them). Maybe the gestures of making art and of translating are attempts at breaking this silence.

I have always been looking for a way to express all the emotions I have been experiencing through this knowledge and presence. That is how I have found possibilities within translation, as I explain in my SKUT essay. I had also previously tried to express those emotions in a short video I made in March 2016. The connection between present space and history, how memory is not past but always in us, with us, within us, has been part of my ongoing quest to better understand myself and the world. It has also been a way for me to explain what literary translation is to me. Why there is an urgency in my gesture of translation, why it is a matter beyond linguistic preoccupations.

As literary translators, we work with material that is many times unknown to us - whether it is because of the subject, the era or geography, the beauty of literary translation is to try to find our place within a text, and settle there for the period language allows us to. In creating connections through our emotions and how we experience space and time, we find a home, and we create one for our readers. My Mokum, some place else for you. We will all come from different realities, yet, in the realm of literary translation - where that connection materialises - we find our common language and create a collective memory and imagination that can live today.

I believe this is exactly what Steve McQueen did with Occupied City: he kept us in the present, inviting us to engage with issues that have unfortunately not disappeared, such as hatred for the “other”, division and polarisation. Violence. He did this, never once showing violence and hatred, never posing any judgment as he made us feel Historydeep in our bodies. By doing so, he has opened the possibility to engage with contemporary societal issues which are directly related to our common past, from systemic racism and violence, anti-capitalist struggle, to the rise of extreme right discourses. He has brilliantly connected our imagination of the past with what matters today. And that is also what I believe literary translation can and must do. This is why, in my imagination, artist and filmmaker Steve McQueen is now also, a translator.

Writer, Literary Translator, Artist based in Amsterdam.

Canan (she/they) publishes The Attention Span Newsletter, taking the time to reflect, to analyse and to imagine our societies through writing, art and culture; and City in Translation, fostering discourse and conversations around the art of translation.